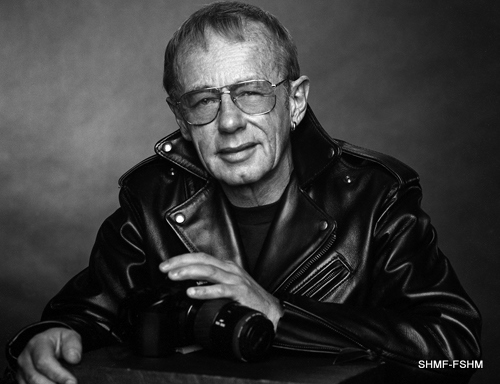

Portrait of Freeman Patterson, Strathbutler 1997 (photo – James Wilson)

… seeing, combining and creating them as integrated “wholes”, will remain a life-long challenge …

Freeman Patterson, awarded the Strathbutler in 1997, is a world renowned photographer, environmentalist, author, educator and humanitarian.

Patterson has long been a champion for the arts in New Brunswick. Patterson’s mastery of photographic techniques allow the viewer to contemplate the landscapes of the natural world with sensitivity. His images of temporal landscapes serve as metaphors tracing the timeless experiences of humanity. Patterson is as much a teacher as an artist of the photographic medium. He has authored ten books on photography and offered workshops in Canada and in Africa.

In selecting Patterson for the award, the jury noted that his advocacy for the arts, his dedication to education and his environmental stewardship have had a profound impact on the culture of New Brunswick. Patterson’s list of honours and accomplishments is long and distinguished. Some highlights of his career include: National Film Board Gold Medal for Photographic Excellence; Doctorate of Letters UNB; Doctor of Civil Law Acadia University; elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Art; Progress Medal of Photography of America, Fellowship Photographic Society of Southern Africa and the Order of Canada.

- A Gallery of Freeman Patterson’s work

- Freeman Patterson Biography

- All posts on Freeman Patterson

- Website: freemanpatterson.com

Patterson served for six years as a trustee of the Nature Conservancy of Canada as well as donating his property at Shamper’s Bluff to the Nature Conservancy so that it will remain an ecological reserve and education area. He was awarded the New Brunswick Conservation Council’s Milton Gregg Award for environmental stewardship.

After winning the Strathbutler Award, Freeman Patterson was invited to serve on the Board of Directors of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation and continues to guide the Foundation in its philanthropic work.

In the artist’s words

Every artist is, first of all, a craftsperson thoroughly knowledgeable about the materials, tools and techniques of his or her particular medium and skilled in using many of them.

However, in my view, no amount of technical knowledge and competence is, of itself, sufficient to make a craftsperson into an artist. That requires caring –passionate caring about ultimate things. For me, there is a close connection between art and religion, in the sense that both are concerned about questions of meaning. – If not about the meaning of existence generally, then certainly about the meaning of one’s individual life and how a person relates to his or her total community / environment. This is not to say that every work of art is or should be a heavily profound statement; indeed it may be very light-hearted, but rather that consciously and unconsciously, an artist engaged in serious work is always raising or dealing with the question, “What really matters?”

For me, answering the question means recognising factors that produced and shaped me. I cannot escape dealing with these things if I am to live creatively as a human being, or to put it another way, if I am to take control of and maintain the integrity of my own life. Photography (and, more generally, visual design) has been my enabling medium

In the broadest sense, I photograph Nature-which includes human beings. Growing up in a rural community, I was surrounded by natural things. Unlike a child in a totally urban environment, my friends and peer group were not only other children, but also wild and domesticated animals, plants of every sort, brooks and waterfalls, rocks and sand. In winter, I listened to the wind-chiming of ice-covered branches; I wandered through spring’s greening fields, splashed about for minnows in the river and gathered bouquets of autumn leaves.

However, the obviously beautiful in my environment was balanced with other realities. I saw the food chain operating, experienced the effects of droughts and floods, and daily observed the process of aging. When my little sister died, the loss I felt was assuaged by my having learned early that this happens to everyone and everything.

I believe that the ability of human beings to be creative depends fundamentally on the health and wellbeing of our biosphere-the few kilometres of air, water and soil that surround our planet like the skin of an apple. Quite simply, they are the physical and spiritual bases of our lives and the as only source of materials and tools that enable us to express our responses to questions and feelings about ultimate things. Creation and creativity are inextricably linked.

This awareness now forms the central core of my work. The abstracting of visual elements in order to recognise their particularity has become automatic; but seeing, combining and creating them as integrated “wholes”, will remain a life-long challenge.